Achieving Giftedness

/When my first child was entering kindergarten, I suspected she was gifted, but I was afraid to say so. It sounded so pretentious and loaded. So, I skirted the issue. In our own small classes, I took a front row seat to her excited drive to learn. We taught her to multiply in kindergarten, construct geometry proofs in first grade, and her reading level skyrocketed in second grade. In a multi-age classroom, she learned history, science and Latin well beyond her grade level from a buffet of interesting content. After graduating eighth grade, she enrolled in a traditional high school and found herself disheartened that teachers “spoon feed” information instead of giving her an opportunity to make the connections herself.

With my second child, I had the same inclination. As early as age four, I knew he was thinking deep thoughts when he confidently declared, “a shape must have more than two sides.” I enrolled him in our school as well, and his test scores show him above grade level in every subject. But is he gifted?

Years ago, a second grader enrolled in our school who had memorized the atomic numbers of each element, the diameters of every planet and investigated college level math for fun. His cognitive ability was “off the charts.” Another student learned Spanish, Greek, Latin, French then Esperanto for fun on her own. If these children are the standard of giftedness, there’s no comparison.

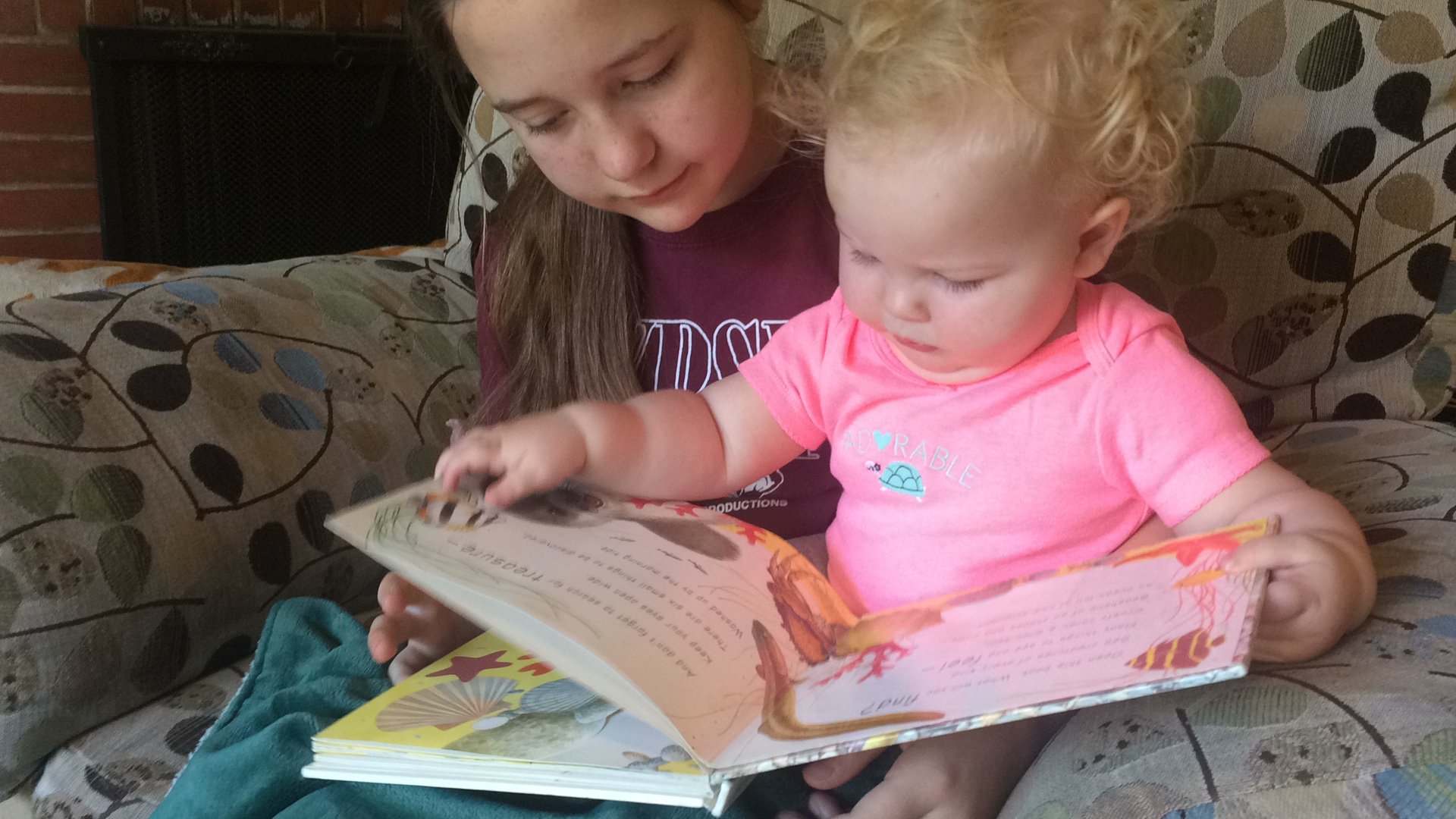

Now that our third child is entering kindergarten, we're asking the same question. We were shocked that she could write her name at age four, but did she really know all the letters? This motivated a deep dive of research: what makes a child gifted?

We landed in the pages of the gifted educator’s bible, Growing Up Gifted by Barbara Clark. Written and revised from the late seventies until 2012, it contains a wealth of research and guidance.

I assumed that a child was born gifted, but Barbara Clark demonstrates that “nurture” has as much, if not more, to do with it than “nature.” We parents have great influence over not only our children’s physical and emotional health but their mental capacity as well. In both genetics and environment, the term gifted, by its very nature, is something a child receives passively.

We’re all born with the same basic wetware in our heads, 100,000,000 to 200,000,000 neurons ready to connect to one another to make sense of the world in what ends up being our own unique way.

Imagine an elevator that takes the same exact amount of time to get from the ground floor to any other floor. Push the 30th floor, wait 30 seconds. Push the 18th floor, 30 seconds. Push the 2nd floor, 30 seconds. The first 10 seconds are the fastest part of the ride, then it coasts slower and slower to a stop when the doors open. It’s very fair, if inefficient.

Likewise, in the first four years of a child’s life, her brain achieves around 50% of her adult capacity for intelligence, 80% by six, and by eighteen she’s about as intellectually developed as she’ll be for the rest of her life (with some room for improvement or decline over the long term).

Here’s another metaphor. Hurricane predictive maps have a characteristic cone graphic that shows potentially affected areas. It indicates where the storm may end up with bounds on the uncertainty. Within the range of each child’s potential, it is our contributions as parents and (the lucky ones) teachers that determine their achievement. So, here’s some helpful advice.

Parents of Toddlers & Preschoolers

Little by little help children understand feelings and desires of other family members including yourself. Use big words, varied vocabulary and clear communication, and help them express their thoughts in complete sentences, too. Celebrate the accomplishments of each family member without comparison. Involve young children in planning family trips and decisions so each person’s contribution is valuable.

“Although genius may not result, there is every reason to believe that a level of giftedness may be attainable for many children.” (Clark p. 37)

Parents of Kindergarteners

Experts suggest IQ or aptitude testing at age six to determine giftedness early. However, many schools do not offer differentiation for gifted students. Budgets are tight in private and public schools. In 2013 the State of California canceled funding for the state GATE categorical program, leaving the fund allocation up to the local public schools. Ask your school what accommodations they offer gifted students and what the criteria are to qualify.

Parents of Elementary Students and Up

If your child is not engaging well in the classroom, investigate. Get them tested by a neurologist. Consider other educational options that will stimulate their intellect. They need positive challenges and time with intellectual peers (whatever their age) to strengthen their mental muscles at their own level so they don’t atrophy. Carol Dweck coined Growth Mindset to describe the best outlook a child can develop. This takes a very special classroom environment.

If your child is wasting time at school, investigate. Barbara Clark found this gem: as early as the 1940s it was observed that moderately gifted children waste nearly half of their time in a regular classroom and profoundly gifted children waste almost all of their time. When challenging academics is lacking, students find other ways to challenge themselves, sometimes with misbehavior. And when classwork is consistently easy, gifted kids expect that to always be the case. Then when faced with a difficult task, they have an intellectual identity crisis, “Maybe I’m not as smart as I thought.” And they shrink from the opportunity.

Advocate for your child. Find out how you can contribute to their classroom environment and keep their home learning environment safe and rich. Then see where your little hurricane lands!

Also published in the column Live & Learn, The Crier, Southern Marin Mothers Club, June 2022