Rich Content Strengthens Gifted Students

/A student recently came to Chronos Academy from another school where he felt pretty unsatisfied with the content he was learning. During a science lesson on the water cycle, he had lamented in utter frustration, “I learned this in preschool!” It reminded me of my own childhood.

I was at my cousin Rose’s house while her neighborhood friend was over for lunch. We were talking about anything and everything when my new friend asked, “Do you read the encyclopedia?” Surprised it was even optional, I replied, “Of course!”

I was in kindergarten.

When I was young, I was an insatiable learner but a terrible student. I refused to do homework but spent my after school hours at the library devouring books or learning on my friend's computer. I was completely turned off by mundane lessons on topics I had heard before or studied on my own.

Even as an adult, every day I take a deep dive into some new subject. I just can’t stop. Not learning is the equivalent of a runner not exercising his legs or a musician not practicing.

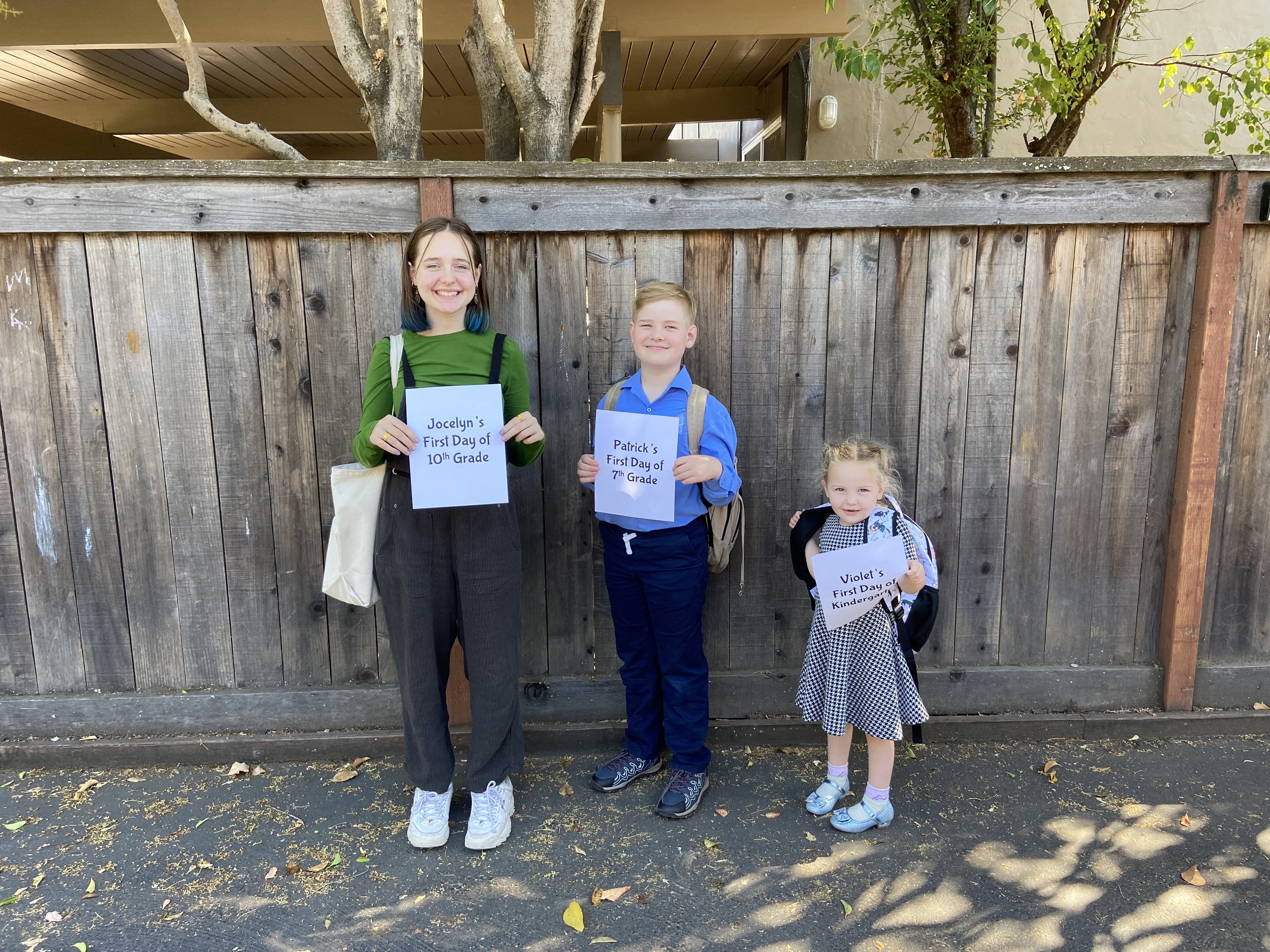

Gifted students crave learning. And they truly need that stimulation in order to maintain their wellbeing. They are the children who exhibit anxiety because they are bored. Their internal drive cannot abide sitting in neutral gear; what will they do with themselves that is true to themselves while they wait? They are sprinkled in all schools and grades but they just don’t fit.

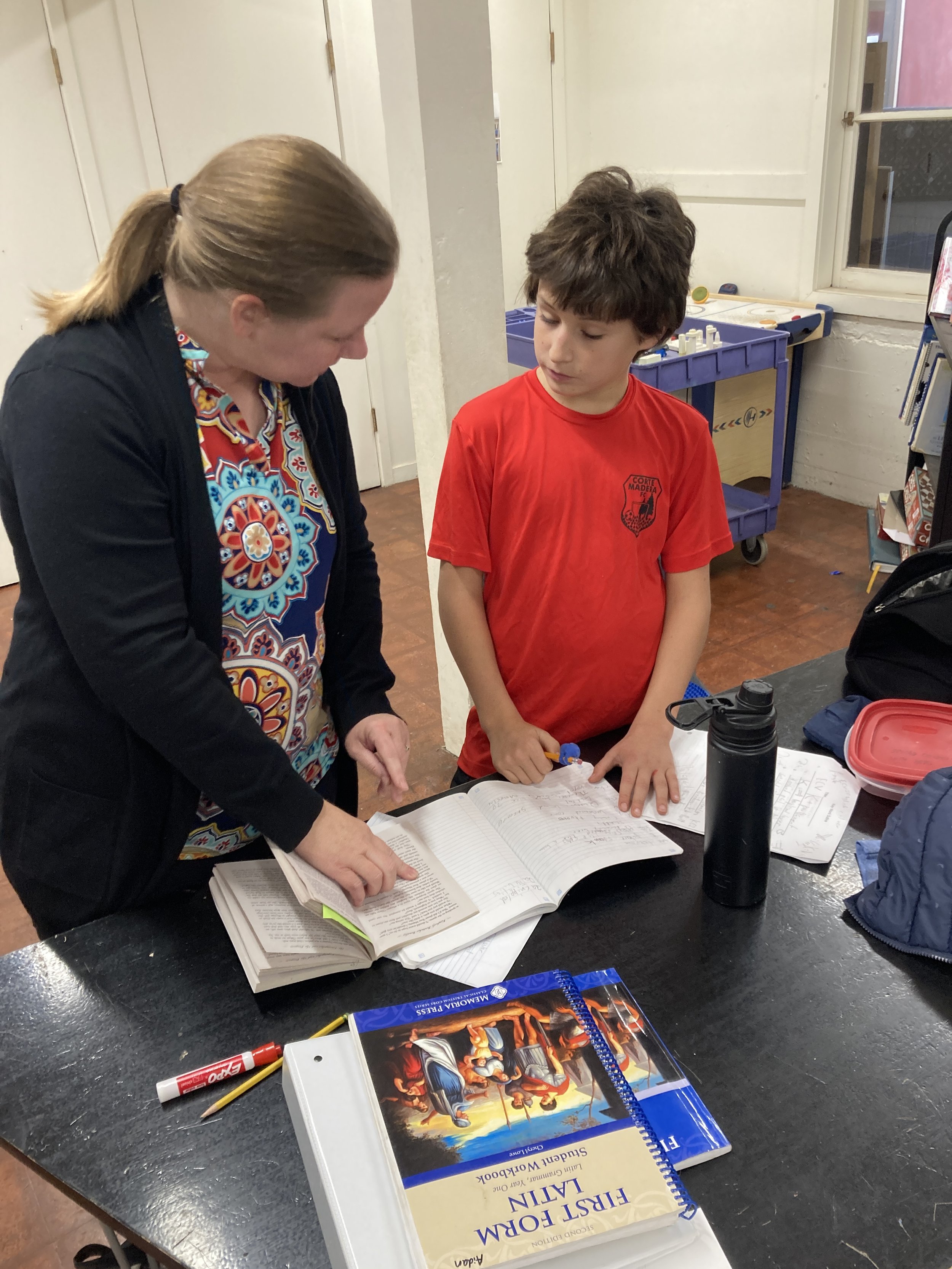

Classroom teachers do their best to meet each student at their level, but unfortunately a traditional curriculum cannot easily be adjusted to be deeper and more challenging. In order to meet the needs of gifted students, teachers must find or write lessons specifically for them. With so many other demands on their time and attention, this is unsustainable.

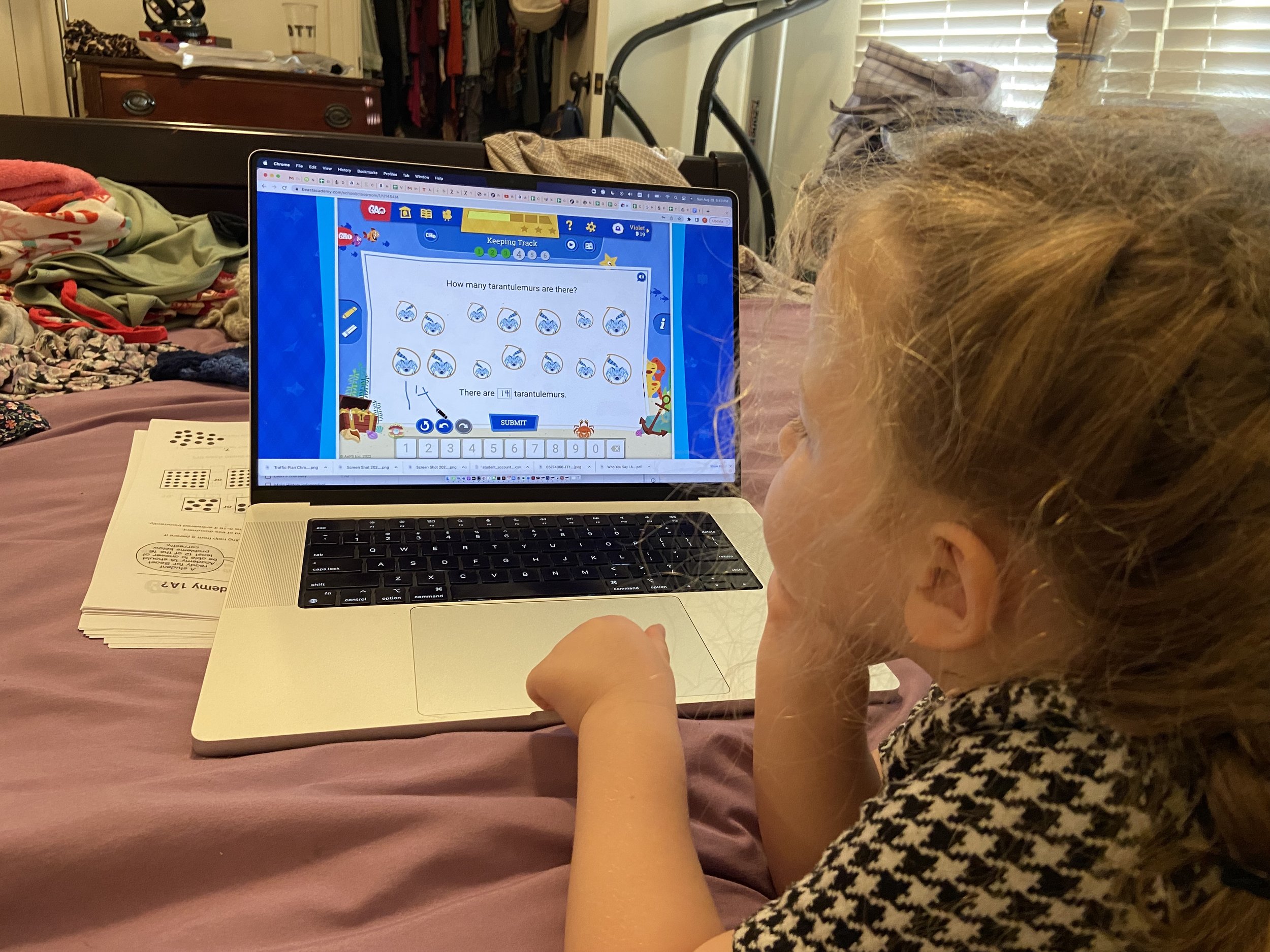

Gifted students need a completely different approach. Chronos Curriculum starts with a rich deep content that would seem rigorous to most adults and then scales it down to each student’s individual level. Kids ages 4-14 learn a timeline of human innovation, the stories of the innovators and the concepts they developed in bite size portions just right for them.

For example

We write argumentative essays on careful reading of Rumi’s Masnavi.

We study Pascal’s, no, Yang Hui's, no, al-Karaji’s triangle.

We recreate medieval scientist Pierre Peregine’s compass according to his notes.

We are curators of the arts, sciences and lives of our forebears. We guide our students into readings, mathematical explorations, and artistic emulation that connects them with the best humanity has produced. Educators at Chronos Academy practice this daily, pointing to people who epitomize the qualities we hope to engender within our classrooms.

The depth and breadth of human discovery is all of our heritage, and it is increasingly available to us. Universities, museums, even math associations are sharing and translating more and more of their collections online. We have everything we need to bless our children with rich content to strengthen them into learning champions!