Healing Joy Bonds

/2020 was a very difficult year for all of us, but it was earth-shattering for our daughter. Seventh grade was such a big year already; she was adjusting nicely to puberty, her first cell phone, babysitting her 3-year-old sister, and “hanging out” with friends with new independence.

Then disaster struck. Our church dissolved, and with it, her identity group. COVID hit, and her independence dissolved, too. School moved to Zoom, and her social life dissolved. Then when Grandpa passed away, we suddenly moved in with Grandma in Oklahoma. Her privacy, her routine, and her safe haven all dissolved. She felt stuck – stuck on Zoom all day, afraid to get in trouble for not paying attention in class; stuck babysitting her sister while her parents helped Grandma sort through Grandpa’s stuff; stuck in another state with no way to get back to her intricately decorated bedroom. And, having not lived through many crises, she wondered if shelter-in-place was her new normal, forever.

She reacted silently. She stifled her frustration. She babysat but didn’t engage with her siblings. She cooked for the family but pretty much stopped eating. She taught herself ukulele on YouTube but then surfed mindlessly. She chatted and FaceTimed friends but got lonelier. She photographed self-portraits in the beautiful Oklahoma sunsets to validate her existence. She carried a heavy weight of expectations, criticized herself for not doing more, attempted to cope, isolated herself and pretended to be fine. She spiraled into obsessive compulsive disorder, and we had no idea for months. Our confident, friendly, empathetic girl became anxious, angry and depressed.

Her story is not unusual.

In December 2021 the Surgeon General observed that the “pandemic intensified mental health issues that were already widespread by the spring of 2020.”[1] Screen time is a key factor; online interactions cannot satisfy a teenager’s need for connection. Despite spending more time relating on social media, teenagers are reportedly lonelier than any other age group. As of October 2021, experts declared a national health emergency in young mental health.

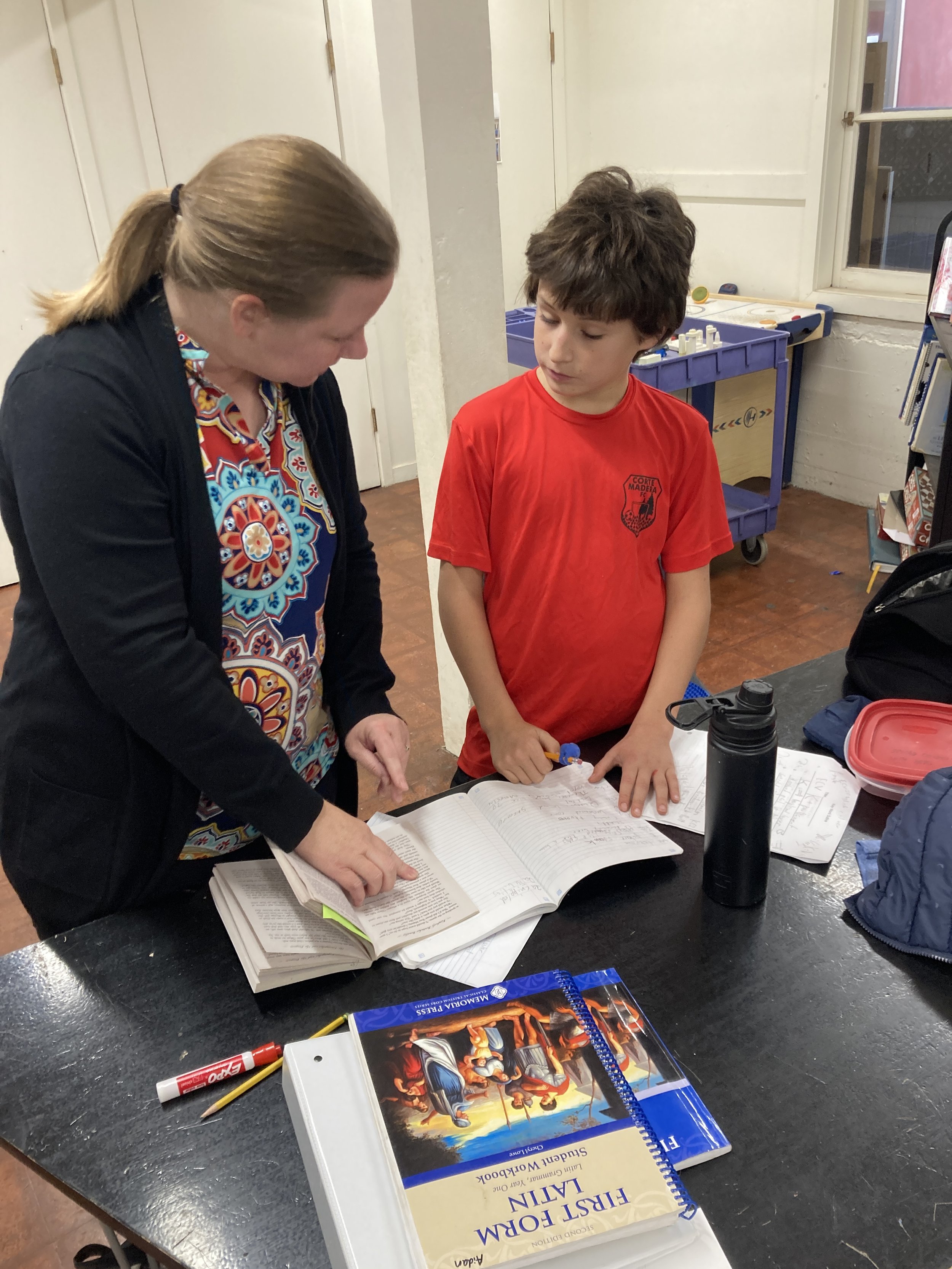

A boy enrolled in our school last year with anxiety that was crippling his academic progress. Although highly gifted, he could not tackle skills that were challenging for him and often hid under his desk to read instead. In our small class, we allowed him to wiggle without judgment and encouraged him to engage. We nudged him to write essays by allowing him to dictate to a teacher. We encouraged him to do weekly presentations in a gentle, supportive way without a heavy expectation that he should already be able to.

Another boy enrolled after a year of school avoidance. Because of anxiety he could not leave the house to go to school. Our small classes are much less intimidating, but he froze at the door on the first day. He made it over the threshold when we agreed to let his Chinese pug attend with him for two days.

As teachers, we’re up to our waists guiding our students through the muddy waters of unprecedented trauma[2]. We asked our middle schoolers how many of them had been bullied in the last year, and they all raised their hands. Tears are not unusual during the school day. Students work through challenging conflict resolution several times a day. Teachers, not counselors, we collaborate with consultants, cooperate with counselors and conference with caregivers to help kids heal. The defenses are finally coming down, and we’re seeing real empathy and real connection. These lessons are so much more important than academics.

When we moved back home from Grandma’s summer 2020, we expected our daughter to return to her cheery self. She volunteered at our summer camp, took walks with friends and helped potty-train her little sister, but she was still suffering. For months, she couldn’t figure out how to ask us for help. She and her friends all applied to private schools, but she was waitlisted and devastated. Her closest friend pulled away, and she felt isolated again. We thought she was experiencing mood swings typical of a teenage girl, but on a weekly walk with a mentor, she indicated there was a bigger problem. A year later, we offered to find her a therapist, but she got worse not better. Transitioning to high school offered even more stress. After a year of therapy for general anxiety, she was finally diagnosed with OCD. Eighteen weeks of pretty intense Cognitive Behavioral Therapy trained her to resist compulsions and ignore intrusive thoughts; she now has the tools she needs to cope.

We thought the problem would be fixed, but daily recovery is overwhelming to her on top of school work, musical groups and friend drama. She is not recovering day by day, rather through cyclical progression and regression. My tendency is to assume misbehavior. But kids are almost always trying their best, but just don’t have the tools, energy or the capacity to change their behavior.

We’ve learned from the field of Interpersonal Neurobiology[3][4] that a person grows strong in joyful connection with others. “Relational joy is the engine that drives thriving, recovery and even produces the strength needed for prevention of trauma and addiction.”[5] Our first task is to take pleasure in being with her; she needs relational fuel to grow through her weaknesses. She just can’t do the tasks on her own at age fifteen. And she doesn’t want her parents’ help at age fifteen either. But she deeply needs her parents’ love.

So here is our daughter’s advice to you if your child begins to deal with mental health issues.

“Don't try to fix it. You’ll make it worse. Listen carefully. Things sometimes get worse before they get better. Don’t stress about a linear recovery. Relapses are normal. Don’t pressure them to do what you think they need to do. Empower them with options so they don’t feel stuck. Don’t force connection, but encourage them to spend time with people. Be available as much as possible to connect, just listen, sit quietly or cry together.”

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/07/science/pandemic-adolescents-depression-anxiety.html

[2] https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/01/special-childrens-mental-health

[3] https://www.allanschore.com/

[4] https://drdansiegel.com/

[5] https://lifemodelworks.org/jim-wilder/

Originally published March 2023 issue of The Crier, Southern Marin Mothers’ Club.